In matrimonial cases, at times one spouse may hide assets from the other spouse and fail to provide full and frank disclosure of such assets, especially when the marriage is breaking down and divorce seems imminent.

Often a spouse fails to provide disclosure of his/her assets as he/she would not want such assets to be included in the pool of matrimonial assets available for division and distribution by the Court during the second stage of a divorce proceeding regarding ancillary matters. At this second stage, both ex-spouses are required to file an Affidavit of Assets and Means to disclose a full list of assets held, whether in joint or their sole names.

However, the Court has the power to draw an adverse inference against either spouse whenever he/she has failed to make full and frank disclosure of his/her matrimonial assets as held in the seminal Singapore Court of Appeal case of ANJ v ANK [2015] SGCA 34 at [29]. The drawing of adverse inferences is meant not to punish the non-disclosing spouse but is adopted to further the aim of a fair and equitable distribution of assets between the ex-spouses, under section 112 of the Women’s Charter, by depriving the non-disclosing spouse of the benefit of that improper conduct (CHT v CHU and another appeal [2021] SGCA 38 at [6]). It is for the Court, not parties, to decide whether a particular asset belongs in the matrimonial pool. Thus, regardless of parties’ subjective views on what is a matrimonial asset, parties must assist the Court to arrive at the correct decision by making full and frank disclosure (USB v USA and another appeal [2020] SGCA 57 at [58]).

The Court would draw an adverse inference where two requirements are met:

(a) there is evidence which establishes a prima facie case against the spouse against whom the inference is to be drawn; and

(b) that spouse has some particular access to the information he is said to be concealing or withholding (Koh Bee Choo v Choo Chai Huah [2007] SGCA 21 at [28]).

For requirement (a), there must be some evidence which suggests on its face that the spouse in question has deliberately sought to conceal or deplete some assets which would otherwise be available for division (BOR v BOS and another appeal [2018] SGCA 78 (“BOR”) at [75]).

Adverse inferences have been drawn by the courts where a spouse failed to provide evidence of any returns received upon disposal of certain properties (TQU v TQT [2020] SGCA 8 at [139]) and where there were withdrawals of significant sums of money from bank accounts

(UMU v UMT and another appeal [2018] SGHCF 16 at [33] and [35]). However, not every unexplained withdrawal or decrease in value in a bank account over time will be sufficient to raise a prima facie case of depletion of assets. Courts would generally disregard withdrawals of money which may legitimately be explained as personal expenditures or as genuine expenditures on business or investments (BOR at [76]).

There are generally two approaches the Court can take to give effect to an adverse inference against the non-disclosing spouse. Firstly, the Court could make a finding on the value of the undisclosed assets based on the available evidence and include that value in the matrimonial pool (“the quantification approach”). Alternatively, the Court order a higher proportion of the known assets to be given to the other party (“the uplift approach”) (UZN v UZM [2020] SGCA 109 (“UZN”) at [28]). The Court would adopt the approach it considers most appropriate in achieving a just and equitable division of the true material gains of the parties’ marriage. Thus, the approach to adopt would be a matter of the Court’s judgement in each individual case (UZN at [29]).

This article will focus briefly on the uplift approach. The uplift approach seeks to eliminate the effects of non-disclosure by awarding a greater share of the total pool of known matrimonial assets to the disclosing spouse (UZN at [34]). The uplift approach is generally adopted where there are no details available to be able to make a reasonable quantification of assets that remained undisclosed (VSN v VSO [2021] SGFC 70 at [103]). In practice, any adjustment of the ratio for the division of the matrimonial assets under the uplift approach has an effect equivalent to adding some corresponding value of undisclosed assets to the matrimonial pool under the quantification approach (UZN at [35]).

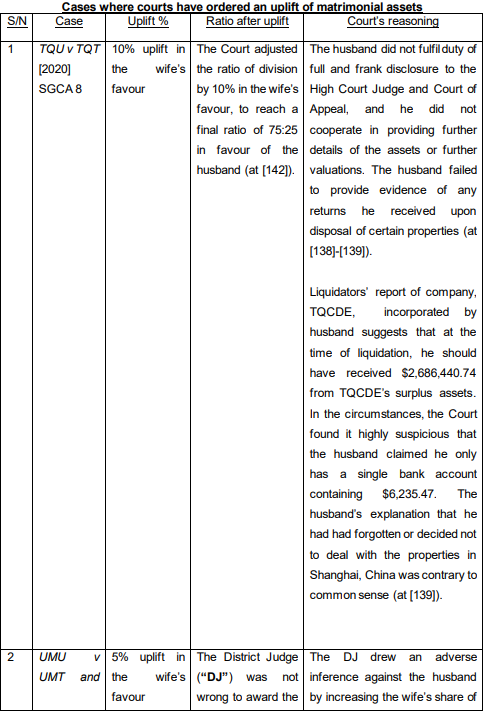

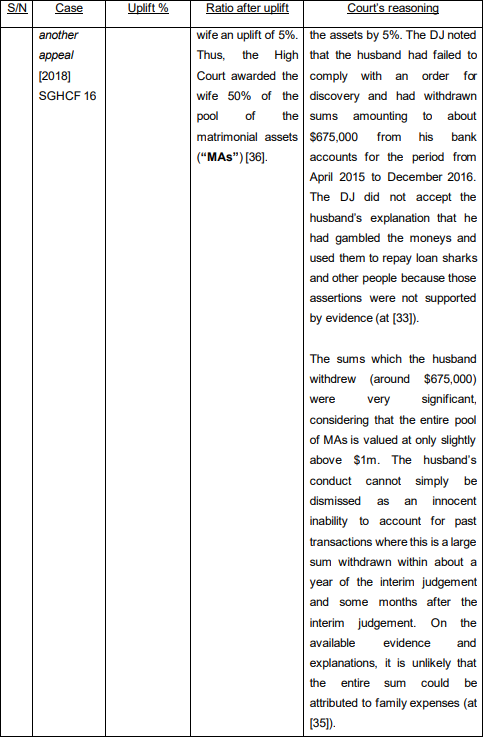

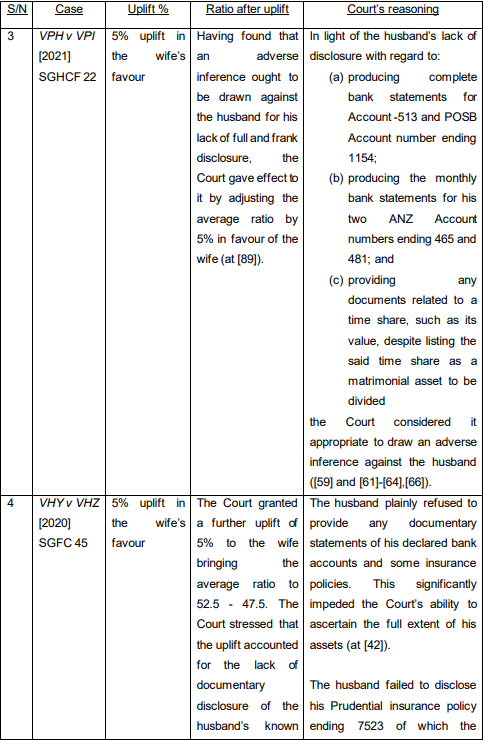

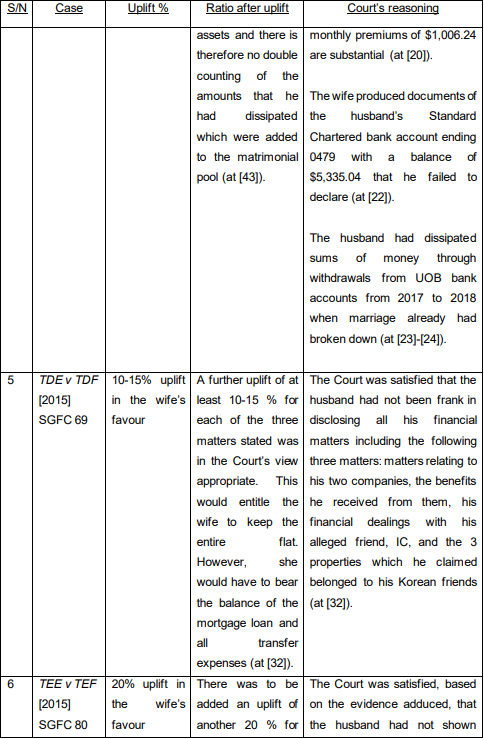

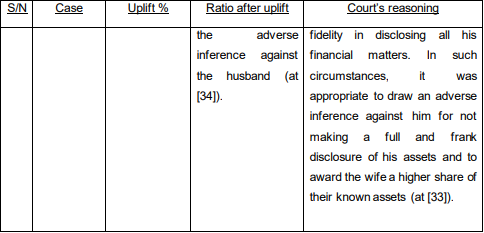

The cases adopting an uplift approach cover a broad range. Uplifts ranging from 20% are not unprecedented (TME v TMF [2016] SGHCF 6 at [59]). Where there is an uplift of 20%, the ratio of assets awarded to the disclosing spouse increases by 20% with a corresponding 20% decrease in ratio of assets awarded to the non-disclosing spouse. In the final analysis, much would depend on the facts of the case, and in determining the appropriate uplift, one of the guiding factors for the Court would be the evidence before it as to the extent of non-disclosure relative to the value of the disclosed assets (TYS v TYT [2017] SGHCF 7 at [45]). Below is a table providing a brief summary of past cases where the courts have ordered an uplift of matrimonial assets in favour of the wife.